How to sum up the life and times of Ian “Molly” Meldrum? If you think four hours is an extraordinary chunk of airtime to devote to a television biopic on the cat in the hat, you probably didn’t grow up in the 1970s and ’80s. If you did, you almost certainly grew up on Countdown, the weekly music program that, over 13 years and 563 episodes, made Molly the unlikeliest of entertainment icons.

Molly, which premiered on Channel Seven last night in the first of a two-part mini-series, tells his story ingeniously and, perhaps, with a touch of sly irony: via a series of flashbacks, following Meldrum’s terrible accident at home in 2011, which left him with severe injuries. (At the time of the show’s airing, Meldrum is recovering after a second fall in Thailand).

It allows for an unashamedly nostalgic, but also unexpectedly affecting look back at an era that was both more innocent and less straight-laced. As a gormless young suburban boy, I mostly took even Countdown’s most anarchic moments at face value. Even so, I’m pretty sure it wasn’t just the infamous 100th episode when its host – not to mention its guest stars – turned up on set considerably the worse for wear.

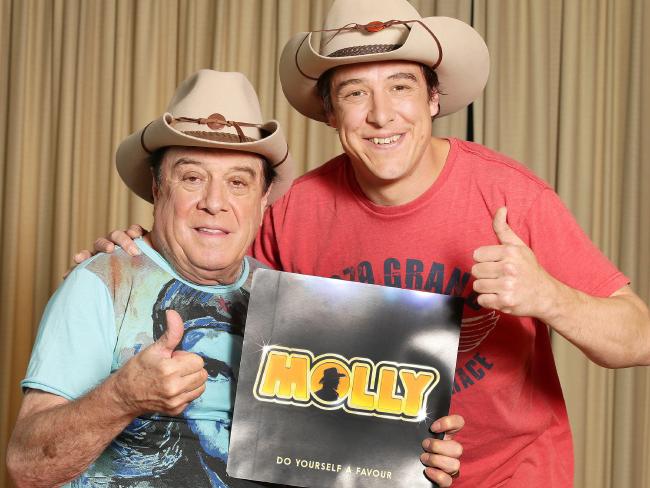

With his craggy features, Samuel Johnson was born to play Molly. More impressive than the physical resemblance, though, is the genuine pathos with which Johnson invests in the character. Underneath Molly’s bumbling, stuttering exterior (his first word on air is “um”) lies an intuitive intelligence and the irrepressible enthusiasm that audiences came to adore him for.

He’s also fiercely – and physically – loyal, which gets him into trouble both with the law and his superiors at the ABC, especially buttoned-down executive Alan Wade, played with perfect rectitude by Benedict Hardie. He is ably protected by Countdown’s producers, Michael Shrimpton (Tom O’Sullivan) and Rob Weekes (TJ Power), whose main job seems to be to save our hero from himself.

The show touches delicately on his early family life: Meldrum is raised mostly by his grandmother, after his mother is hospitalised due to an unspecified mental illness. Then, of course, there is his sexuality, which became a talking point last month after Johnson told the ABC that a scene in which he kisses another man had been cut by Meldrum himself, who thought it was “gratuitous”. (“I wanted the kiss in, I wanted it to be in there, it wasn’t gratuitous at all,” Johnson said.)

As our first sexually fluid television star, Meldrum never really came out, because he never really had to – what you saw was what you got. Here, the subject is dealt with mostly via a series of nudges, winks and knowing looks, until a touching scene where Molly, who is engaged to Camille (Rebecca Breeds) takes his strung-out, heroin-addicted transgender housemate Caroline back to his backwoods Victorian home town of Quambatook, only for both to accuse each other of running away from themselves.

It’s these glimpses into the man behind the mononym that made the first episode of Molly so much more satisfying than Never Tear Us Apart, the INXS mini-series from 2014. We see his self-doubt – “If this falls apart, no one’s gonna give me another chance,” he confesses to Camille before Countdown’s debut – and more obscure details, like his lifelong obsession with Egyptology and the St Kilda football club.

In between all this is the music. Countdown’s influence on a generation of Australian music – both for better and worse – is incontestable, and Meldrum, for over a decade, was at the centre of it. (This extended to his role as a producer – both on Russell Morris’s epochal flower-power hit The Real Thing and Supernaut’s bisexual anthem I Like It Both Ways.)

The structure of Molly allows for Countdown’s most celebrated appearances and controversies to be gleefully recast: the initial appearance of Skyhooks, the endlessly replayed “interview” with a loaded Iggy Pop, and the later refusal of Midnight Oil to appear. Along with Cold Chisel’s trashing of the Countdown awards set in 1981, their withdrawal signalled the beginning of a waning in the show’s agenda-setting power.

But the best moment – indeed, as the man himself had it, the most important moment in the history of the program – was Meldrum’s catastrophic interview with a youthful Prince Charles, during which he repeatedly fluffed his lines, swore, put his hand on the Prince’s knee while calling him “lovey”, and asked after his mum (“You mean Her Majesty The Queen,” came the unctuous reply).

The wonder of this scene is, of course, amazement that it happened at all. But the 1970s were different days, when the ABC still played God Save The Queen before it ceased broadcasting at midnight – but also a time when AC/DC’s Bon Scott, wearing a schoolgirl’s uniform and pigtails, could smoke a durrie while attacking Angus Young with a rubber mallet during a live performance on the national broadcaster.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xi5BKTLU2bQ

Whether inept or insouciant, Meldrum’s treatment of Charles said much about our history and our relationship with our colonial masters. But it also spoke of Molly’s almost comic inability to be anyone other than himself, and his determination to treat everybody – as his grandmother taught him – the same. Molly the mini-series is a funny, warm and wholeheartedly affectionate tribute.

First published in The Guardian, 8 February 2016