Danny Fields – so-called “company freak” of Elektra Records in the late 1960s; the man who discovered the MC5 and then the Stooges; later the first manager of the Ramones – once rapturously described Television as the band with “the most perfect skin in the world.” They literally got under mine: on the inside of my right forearm, I have a tattoo of the design adorning the back of their debut album, Marquee Moon. On the original midnight-blue sleeve, the moon is dazzling; radiating white light. On my pale skin, it’s necessarily polarised. I’m occasionally asked if it’s a black hole.

Television – singer/guitarist Tom Verlaine, guitarist Richard Lloyd, bass player Fred Smith and drummer Billy Ficca – was the first group to play CBGBs, the legendary New York dive that was also the crucible for Patti Smith, the Ramones, Blondie and Talking Heads during its first, glorious era, between 1974 and 1978. Lean, short-haired and dressed in plain clothes, held together at times with safety pins, they were in the vanguard of punk, a movement they otherwise bore little relation to.

If anything, they were the anti-Ramones. Nick Kent, in a famously hyperbolic NME review, cocked them cold when he said to call them punk was akin to calling Dostoyevsky a short-story writer. Released in March of 1977, Marquee Moon anticipated post-punk six months before the Sex Pistols made the form instantly obsolete with Never Mind The Bollocks. To this day, it sounds as urgent and thin and wiry as the band (once) was, filled with ecstatic, extended guitar solos at a time when brevity was the sine qua non of rock & roll.

They made art-rock cool again, and it’s impossible to imagine hundreds of bands, from fellow New Yorkers Sonic Youth and the Strokes, to Australian acts like the Church and Eddy Current Suppression Ring, without them. Now, they’re here in Australia for the first time, firstly to play All Tomorrow’s Parties spin-off Release The Bats in Melbourne (where they perform Marquee Moon in its entirety), and tonight at the Enmore Theatre in Sydney, which promises most of that album – we get seven of the eight tracks – plus a little more besides.

The only absentee is Lloyd, who quit the band in 2007 following a health scare. He’s been replaced by session musician Jimmy Rip, who has played alongside Verlaine in the latter’s solo ventures for years. But the words “No Lloyd, no Television” have been heard, and it’s not mere preciousness. The defining feature of the band was the interplay between Verlaine and Lloyd, whose tough, snappy counterpoints served to earth Verlaine’s explorations – without them, Television would be all crackle and pop. (Mind you, they took turns: this is the kind of band that listed who was responsible for what solo on each of their three studio albums.)

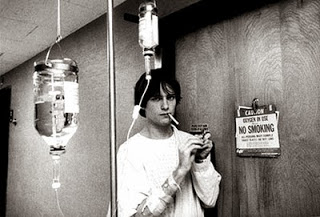

Perhaps also missing is the near-mythological status that accompanies Lloyd as one of the great junkie hellraisers of the New York scene; another contrast to the ascetic Verlaine. Lloyd was the man who wore the infamous “Please Kill Me” T-shirt that ex-band member Richard Hell, who designed it, was too afraid to wear. A photograph of Lloyd, taken at Beth Israel hospital, depicts the guitarist in a white smock, contemptuously lighting a cigarette in front of a “No Smoking” sign, staring at the camera with pinned eyes while hooked up to a drip.

Cannily, their set is front-loaded with songs on which Lloyd took the original solos, giving Rip an early chance to win over the audience. After an almost perfunctory run-through of Venus, the pinging introductory notes of Elevation really kick things off. But the mix is uneven, and Verlaine’s voice – never a strong point – is puny. On record, he’s commanding, even when he squawks like a chicken. On stage, he’s barely trying. It’s a shame, for the former Tom Miller (he renamed himself after the French symbolist poet) is a fine lyricist, albeit one prone to speaking in riddles: as he sings in Prove It: “It’s too, too, too to put a finger on”.

Still, a Television show is all about the guitars. The third song, 1880 Or So, is the only number from the band’s third, self-titled comeback album from 1992, and it’s a real highlight, its dreamy fluency punctuated by a jarring solo from Rip that builds upon the recorded version. Note-for-note renditions is not what this sold-out, solidly middle-aged crowd expects or wants: this is, as the recent Rhino reissue of Marquee Moon puts it, “jazz for the punk-rock set”, and they’re ready to go as far as the band are willing to take them.

Nothing exemplifies Television’s wanderlust so much as their first single, Little Johnny Jewel, its near-eight minutes originally split across both sides of a seven-inch single (a decision that prompted Lloyd to briefly quit the band on its release in 1975, despairing of their commercial prospects). Heralded by Smith’s descending bass riff, it sparks immediate whoops of glee, and is the first selection of the night to stretch beyond 10 minutes. This is the Verlaine show now, producing the piercing guitar sound one-time girlfriend Patti Smith compared to “a thousand bluebirds screaming”.

It’s followed by the taut See No Evil, the first song from Marquee Moon. And it’s on these shorter, more neurotic songs that you realise how loose Television are on stage – a long way from the mathematically precise group that laid down the album’s epic title track in one majestic take, which Ficca thought was a rehearsal. These songs had been performed and rewritten countless times before being recorded; the definitive articles are on the album. Television have not been a full-time concern since 1979; to expect them to re-make the masterpiece live is absurd.

Two entirely new songs, however, give notice that this version of Television is not all about the re-runs. Both tracks, neither introduced by name, are plangent, elastic, near-wordless meditations, anchored by the pulse of Smith’s bass, and a long way from the fiery guitar duels of the band’s early days. Adventure, the band’s much underrated second album (which, sadly, we don’t hear anything from) was a more mellow affair, while the third sounded like a collection of spy themes. The new material is calmer still, the group sounding more like a jazz quartet than a rock band than ever.

But they’re not what people are here for. It’s amusing to see the crowd take a rare opportunity to sing along to a chorus (Prove It); even funnier to see them attempting to dance to Marquee Moon itself, the show’s 15-minute centrepiece, and the one everyone is waiting for: predictably, they get lost as soon as Verlaine takes off for another hyper-extended solo. It’s a trip where he alone knows the destination, but not necessarily how he’s getting there: Kent claimed Verlaine could solo without ever losing the point; here, at times, he does.

They encore with Friction and an off-key rendition of the Count Five’s Psychotic Reaction, a reminder that Television are as indebted to the post-British Invasion garage bands of the ’60s as much as they are to anything more supposedly sophisticated. But instead of a frenzy, it ends in a slow, bittersweet sigh, a whisper: just as Television’s career first seemed to finish, with a 1979 show at New York’s Bottom Line which everyone, except the audience, knew was the end.

While Television are touring, Hell – squeezed out early by a clash of egos with Verlaine, taking one of punk’s great early anthems, Blank Generation, with him – is touting his autobiography. In its epilogue, the band’s original bass player and genuine punk icon recalls a recent encounter with Verlaine: “His teeth looked brown and broken in the night light, even worse than mine (he still smokes), and his face was porous and expanded and his hair coarse grey. I turned away and walked on, shocked.” Even tattoos fade.

this is a great read!